How to Master Just About Anything

Exploring effortless mastery through cognitive science, AI, and eastern philosophy

I’ve learned an important trick: to develop foresight, you need to practice hindsight.

—Jane McGonigal

Intro - A Kick is just a Kick

There’s a little quote from Bruce Lee that has lived rent-free in my head for over two decades. Yes, that Bruce Lee. The most influential martial artist of all time, and a keen student of philosophy too. For many years this particular quote, which talks about virtuosic mastery, intrigued me, fascinated me, and perhaps even tortured me.

It goes something like this:

“Before I studied the (martial) art, a punch to me was just like a punch, a kick just like a kick. After I learned the art, a punch was no longer a punch, a kick no longer a kick. Now that I've understood the art, a punch is just like a punch, a kick just like a kick. The height of cultivation is really nothing special. It is merely simplicity; the ability to express the utmost with the minimum.”

- Bruce Lee

There are at least a couple of ways to interpret this. But the way I’ve always thought about it builds on Bruce Lee’s interest and love for the Taoist concept of Wu Wei, or Effortless Action. Which is similar to the Japanese Zen concept of Mushin, both of which are related to the Indian idea of Sahaja, which all describe a natural, spontaneous, and effortless way of acting and being (as opposed to pre-meditated, deliberate, and effortful thought and action).

While Wu Wei, Mushin, and Sahaja all have broader philosophical and spiritual aspects, our focus today is on the mental and cognitive phenomena that they all identify as distinctive features of people who have attained mastery over things - from martial arts to calligraphy to the tea ceremony and more.

Take Mushin, or “mind without mind”, which talks about acting without the encumbrances of thoughts and emotions that impede natural and instinctive action. However this isn’t asking for mindless action. Far from it. It implies clarity of mind, awareness, and mindful, spontaneous engagement with the world. If this reminds you of aspects of System 1 (fast thinking) in modern cognitive psychology or the concept of Flow as described by M. Csikszentmihalyi, then you’re not alone.

In the next few sections I will connect the dots between Eastern philosophical ideas on mastery, modern cognitive science, and the study of expert performers. For fun, we will also show some similarities with an AI learning phenomenon called “grokking”. In part two we will put all this theory into action with tips and tricks on how to overcome plateaus on the way to mastery.

But first let’s expand a bit on what Bruce Lee is saying.

In Bruce Lee’s conception there are 3 stages in the journey to mastery. Let’s call these the novice, the journeyman, and the master. These stages can be found everywhere and in every discipline: be it the martial arts or playing the violin. A sport like tennis or a craft like pottery. Whether it is brain surgery or F1 racing. It’s the exact same path.

The Novice

In the beginning, your way of understanding, of seeing the world, is naive, basic, and uninformed - but it is also therefore, instinctive and natural. In the martial arts, at first, a kick is a kick and a punch is a punch. You are blind to the underlying complexities of the art. You cannot see the fine grain of detail that reality is overflowing with.

Beginner’s luck is often a result of this spontaneous, reflexive state of understanding where conscious deliberate thought is yet to enter and complicate the picture. At this stage people tend to try to simply mimic the teacher or perform rote memorization without any real understanding of what’s happening.

The Journeyman

In the process of learning the art, you understand there is so much more to a kick, so much more to a punch.

You begin to understand form and technique, and the relationship between speed, power, and precision. You begin to internalize footwork, position, balance, flexibility, follow-through, straight and curvilinear movement. You begin to predict the opponent’s movement, learn to vary your stance, use the appropriate part of the fist or the foot; use momentum and leverage, you learn to activate and strengthen the appropriate muscles and connective tissue, learn the difference between a kick that pushes someone back and one that can crack a bone. You absorb the kinematics and dynamics of moving your body through space and time - the mind-body connection if you will. You get to understand timing and rhythm, patience, breath work, and stillness.

You begin to see the million little ways a practiced hand is different and superior to that which is unpracticed.

A kick is no longer just a kick, it’s so much more. A punch is no longer a punch.

It’s as if a new way of seeing has come to you. You get lost in these details for a long time, maybe years - sometimes learning them unconsciously without being able to articulate how you do something, and sometimes learning the details consciously and struggling to make them effortless and unconscious.

It’s the same thing in any other art or skill or discipline. Take music for example. Most people can instinctively hum a tune, however badly, and clap along with the beat. To a novice, melody is just a sequence of notes, rhythm is just the beat you clap to.

Then you begin to actually learn how music works and your brain begins to grapple with scales and progressions, chords and intervals, time signatures and phrasing. Harmony is no longer just the absence of dissonance. It is the understanding that certain intervals played together evoke certain emotions: play the first, third, and fifth notes of a major scale simultaneously and you have a happy-sounding chord. Flatten the third and you now have a sad sound. Add a major seventh and it’s the dreamy sound of two people falling in love.

Harmony is no longer just notes sounding good together. Melody is no longer just notes you hum. There’s so much more to it.

The Master

In the final stage of understanding, all this immense detail is captured in the fractal gray folds of your unconscious brain. You don’t have to think about which kick to throw and how to do it, it just happens. You don’t have to think about what notes to play in a scale, your fingers move effortlessly to the right notes. Just like you don’t have to consciously think about your breathing, it just happens.

A kick is now back to being just a kick, a punch is back to being just a punch.

The conscious mind is now free to think about more complex things than the mechanics of throwing a kick or the fingering for an arpeggio.

Freed from the conscious effort of thinking about how to move in particular way, a master martial artist can improvise and adapt their strategy in real-time while sparring. A virtuoso guitarist can express themselves freely and tell a story through their music rather than thinking about the mechanics of which notes to play or how to play them.

A surgeon can revise their procedure and improvise in real-time as they react to new problems they discover inside the body. Instead of spending conscious effortful thought on how to make precise incisions or how to tie the right knot or trying to recall the relevant anatomical or physiological information, these and myriad other details are now part of the master practitioner’s unconscious, effortless repertoire of skills.

Hills, Plateaus, and Dips…

Aha moments and Enlightenment

There are a couple of interesting and related things that happen just prior to the transition from journeyman to master.

The Plateau

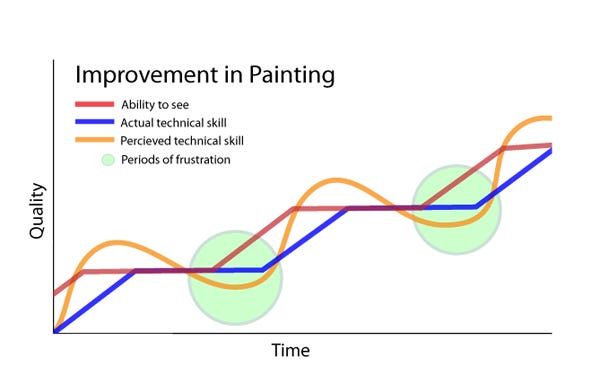

First, progress is rarely linear. Instead, progress comes in the form of steep hills and long plateaus. The hills are where your hard work results in upward movement and visible progress. The plateaus are where your hard work seems to result in no progress at all. You seem to be standing still at the same spot despite all your effort.

The hills are better for progress because your upward movement is noticeable. This is often enough reward and intrinsic motivation to keep the course.

It’s the dreaded plateaus that are littered with the bodies of wannabe masters who simply lost the motivation to keep going. This is, frankly, often the only difference between the journeyman and the master. That is, masters possess the motivation and tenacity (and systems and tricks) to cross the plateaus where nothing seems to be improving despite all the work they put in.

The Dip

Second, just towards the end of the plateau (although you don’t know you’re nearing the end), you suddenly feel like you’re getting worse. Despite all the hard work, there appears to be a noticeable dip in your performance. This is the area of maximum frustration and where most people give up. Often this is because your taste (or ability to evaluate your skill) has outpaced your actual skill

It’s all Circular - The Next Level

Once you cross the plateau and ford the dip, a new hill appears. This might be something you climb instantly (in a bit of an A-ha moment, akin to a feeling of a mini-enlightenment) or you may climb it over time. But unlike the plateau, the progress will be clear and visible, and there is often a retrospective sense of an A-ha.

Unfortunately, soon after you have this mini-enlightenment, you become aware that the horizon has shifted further back. You now have to repeat the whole process again, at the next level of mastery.

Turns out, despite the seeming finality of the word ‘master’, there is no true mastery of anything. Reality is too full of detail for that. The minute you reach an effortless understanding of something, the next level of detail and complexity is unveiled for you. You go back to the starting point, except now it’s the next level. Like a video game.

In the classic book, Art & Fear, we hear the story of David who began piano studies with a Master. After a few months of practice, David lamented to his teacher, “But I can hear the music so much better in my head than I can get out of my fingers.” To which the Master replied, “What makes you think that ever changes?”

Indeed, it never changes. Reality cannot ever be fully mastered. Your taste improves faster than your abilities. Your ability to see the next horizon improves faster than your ability to cross those plateaus and climb those pesky hills of enlightenment.

So why do these plateaus exist? How does something that requires effort become effortless? The answer lies in how our brain has two modes of thinking.

System 1 Thinking

If Bruce Lee had been alive for a few more decades (he died in the 1970s at the young age of 32) he may have seen the connection between the effortlessness described by Wu Wei and modern cognitive psychology’s conception of System 1 (fast) and System 2 (slow) thinking.

This is the idea popularized by Nobel laureate Daniel Kahneman that cognition has at least two distinct regimes: System 1 or fast thinking which is mostly unconscious, spontaneous, fast, reactive, and reflexive, and requires very little or no effort. And System 2 or slow thinking which is deliberate, slow, conscious, reflective, analytical, and therefore effortful.

Examples of System 1 or automatic and effortless cognition are: recognizing familiar faces, driving on an empty road, understanding simple traffic signs, completing simple phrases like “bread and bu____”, feeling fear on seeing a snake, making quick gut-based decisions, etc.

Examples of System 2 or effortful cognition are: learning a new language, solving a complex math problem for the first time, filling out a new tax form, listing out all the pros and cons of a major decision.

Most of our behavior stems from System 1 - we do most things in life without thinking about them. It the kind of processing that happens in the (previously underestimated) cerebellum as opposed to the cortex of the brain1. System 1 is thus related to the effortless action described by Wu Wei.

System 2 thinking is engaged often when you are learning something new. There is a part of the pre-frontal cortex that is activated when we are presented with novelty or patterns not seen before. This kicks it up to System 2 which utilizes a different, more reflective form of processing than System 1. This processing involves a form of conscious analysis that creates a new type of understanding, or mental model, which can then be habituated into your unconscious processing.

System 2 or slow thinking is what makes the Journeyman stage so effortful - where we start to become aware of all the complexities behind a mere punch or kick and have to learn and understand the details from a place of novelty and newness. After a while the System 1 mind is able to connect the dots and create an internal mental model so that you don’t need to be conscious of those things anymore. Your brain has learnt the connections in the Wu Wei sense of natural and effortless grace.

Note that Mastery in this context isn’t just muscle memory, although it’s tempting to call it that. It’s a lot more complex.

The most well-known and robust study of expert performers is the decades long research by Anders Ericsson et al. They studied master violinists, chess players, cab drivers, and surgeons, among other people. It turns out experts are differentiated from non-experts by the richness and depth of the mental representations they carry in their brains.

In fact, the brains of experts change structurally over time. Whether it is a concert violinist, a surgeon, or a London cabbie who can efficiently navigate without a GPS through the maze of 25,000 streets that cross each other haphazardly within 6 miles of Charing Cross, their brains are reorganized to further enable these new mental representations.

Mental Representations & Implicit Understanding

Mental representation is simply another term for possessing an internal model of the world that is relevant to one’s skills. Which is another way of saying that one has an “understanding” of something. This understanding could be explicit, conscious and explainable, which then takes effort to process (System 2), or implicit, unconscious and sometimes unexplainable, which feels effortless (System 1).

I’ve written previously about how all “understanding” is nothing more than connections between concepts. Our understanding grows and becomes more useful/correct if these connections are predictive of how the world operates. Each new level of skill is a new set of threads woven in our fabric of understanding, enabling us to see and do more things effortlessly.

For example, you have a better understanding of music when you know that playing a minor 7th chord will create a bittersweet, reflective sound.

In the Journeyman stage you acquire this knowledge about the minor 7th chord and can utilize it perhaps awkwardly, but you lack the effortlessness, the Wu Wei, it requires to play like an expert, to weave that sound seamlessly into the story you tell through music. When you attain the enlightenment of Wu Wei, this knowledge has become part of your System 1 - your brain has encoded finger movement into pathways that connect with the nature and emotional quality of sound, and hundreds of contexts from other pieces of music, and also with the theory that you can access if needed. A master playing in the moment may not even be consciously aware of accessing this knowledge, they simply play the music.

Interestingly, there is no good name in psychology or neuroscience or even Eastern philosophy for this phase-shift where thinking transitions from having to engage the effortful System 2 to the instinctive and effortless System 1. Gaining Wu-Wei if you will. Specifically, what is the term for the process of crossing a particular plateau and reaching the next level? Let’s try and name this thing in a bit.

Deliberate Practice engages

System 2 to produce System 1 Mastery

By now most people have heard of the saying that you can become an expert in something if you just put in “10,000 hours of practice”. This is, of course, simply untrue. Neither does the 10,000 hour mark (or anything near that number) hold real significance, nor does plain old rote practice (as implied) result in expertise. Malcolm Gladwell, who popularized this “formula” in his book Outliers, either misunderstood the underlying body of research by Ericsson et al that he quotes, or he oversimplified it to the point where it becomes wrong and misleading.

On the other hand, what is almost certainly true is that effort and not innate talent is what differentiates experts from non-experts. Research shows that, barring certain physical limits, innate talent is not required for world-class expertise in most things2. Indeed, all the data we have on expert performers shows that feedback-heavy, progressive, and coached work of a very specific kind called “deliberate practice” is necessary and sufficient for attaining mastery regardless of innate talent.

As opposed to rote practice, “deliberate practice” is the process of painstakingly analyzing and improving from continuous feedback, setting progressive goals, learning from experts and tutors, cross-training, and all the various systematized tricks we’ve come to gather from our study of expert performance.

Even though Ericsson et al don’t speak of it as such, one can think of deliberate practice as engaging System 2 in a very purposeful way and overcoming many of its shortcomings so that we might teach System 1 to arrive at its next A-ha moment.

Bruce Lee is perhaps the ultimate exemplar of deliberate practice - continuously and obsessively studying and analyzing his own movement - practicing, experimenting, cross-training, innovating, and building on various techniques, processes, and ideas until he transcended mere expertise to ultimately create and master his own art form.

The core feature for deliberate practice is refinement under continuous feedback, preferably under some tutelage, plus the various collected tricks it takes to get unstuck from previous, poorer models of the world.

The outcome of deliberate practice is quite remarkably similar to the phase transition of System 2 understanding to System 1, and the kind of effortlessness that Wu Wei is all about.

While sometimes we can skip System 2 understanding and go straight to System 1 (and this happens often through rote practice), Deliberate Practice necessarily has to engage System 2 because the core of deliberate practice is all about analytical reflection from feedback.

OK, but what are plateaus? Why can’t we keep improving linearly with more practice? First, let’s take a little detour through the world of Artificial Intelligence.

Grokking in AI

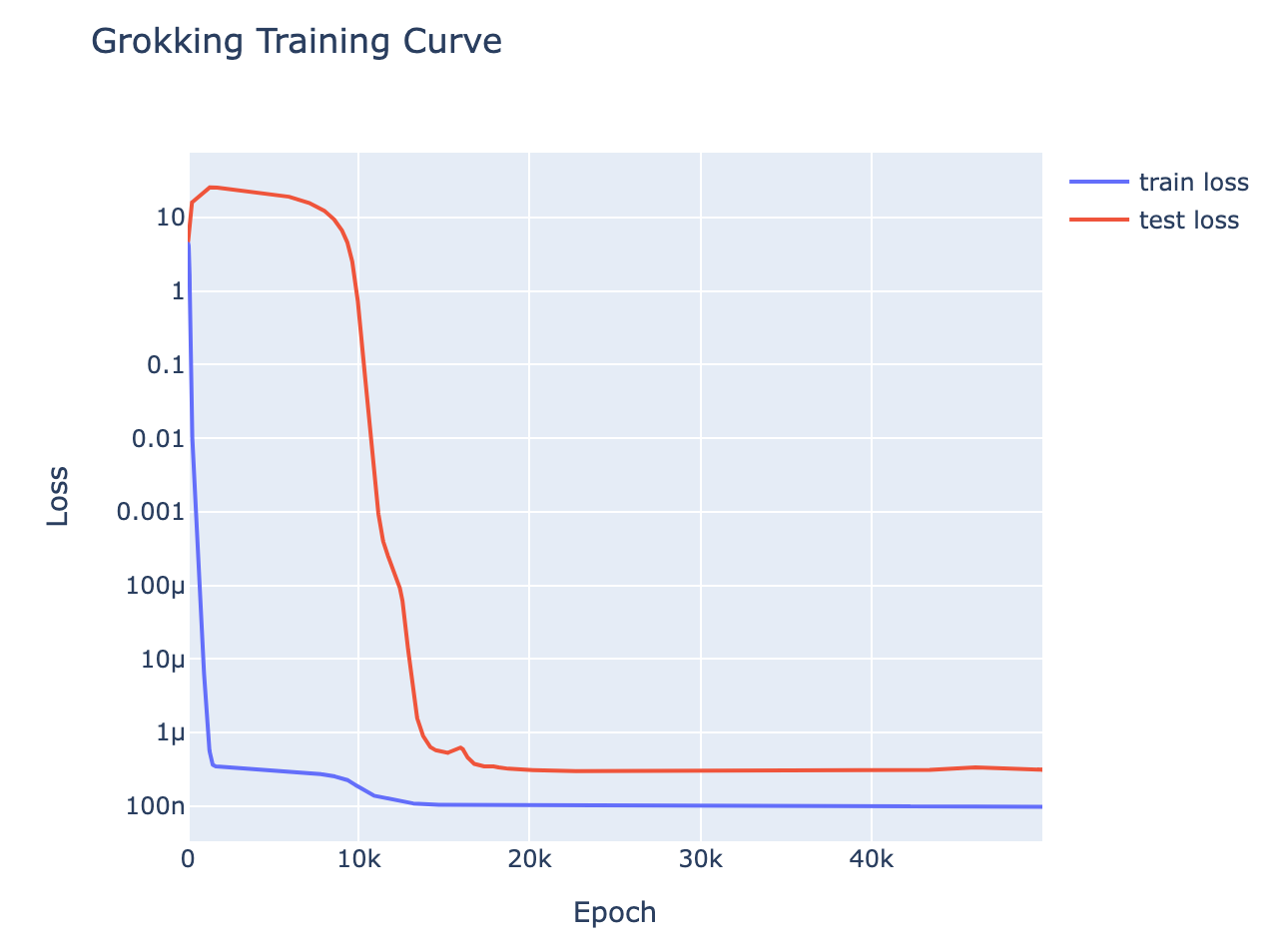

There’s an interesting phenomenon in training AI models called Grokking3. This is where an Artificial Neural Network (ANN) goes through a “phase transition” - from, say, simply memorizing things to actually modeling/understanding the relationship between its input and output.

Grokking is best described in a 2022 paper by researchers Neel Nanda and Tom Lieberum who trained a very simple transformer model (a toy form of the AI underlying ChatGPT) to do “modular addition”. That is, to add two numbers and then find the remainder when the sum is divided by some number. In this case they chose to divide the sum by 113. That is, they gave the neural network a set of training examples consisting of two numbers and also gave it the correct answer as the expected output. The neural network had to look at all these examples and learn the relationship between the input and output. If it truly understood the problem then it would give correct answers to test questions that it hadn’t seen before.

At first, the system cheated. It simply figured out how to memorize all the examples in the training set and could answer the training questions perfectly, but couldn’t extrapolate to new, unseen test questions. But as they kept training the network, repeatedly showing it the exact same training data, something curious happened. After a long plateau of no improvement at all, it suddenly underwent what’s called a phase shift. It “grokked” the relationship between the input and output. With this new understanding of “modular addition” it began to perform perfectly on unseen test questions.

By reverse engineering the neural network the researchers discovered it had learned to add in a remarkable way. Instead of summing and calculating the remainder, it was instead performing a Fourier transform and using Trigonometric identities to come up with the answer.

As Michael Neilsen says, “this is a radio frequency engineer or group representation theorist's way of doing addition”. Nobody had programmed or taught this method to the network. It just happened to be the simplest model that could explain the data - that is, it had the greatest predictive power or understanding of modular addition with the simplest explanation for its answers.

The neural network had learned to do modular addition like an alien from Mars instead of an elementary student from Earth. Unlike the child who learned to add after years of reciting number lists and counting objects using their ten fingers, the AI understood the assignment in a radically different but equally correct way. Perhaps in an even more correct way, given that it doesn’t have ten fingers.

But before it figured out the formula, it was faking the answers - doing rote memorization and thus failing on unseen test questions. Its initial understanding of the world was like the novice who mimics the teacher and performs rote memorization.

Due to an interesting feature of the learning process called regularization (it seeks to find the simplest/smallest model that can explain the data) it had an A-ha moment, arriving at its informed Wu Wei mastery of the task at hand.

Of course I do not imply that this is actually what is happening in our brain. I provide the analogy because (a) it’s fascinating to me, and (b) our understanding of things generally benefits from metaphors even though they can sometime be incorrect and misleading. My goal is to understand the shape of things better by using unexpected frames and different perspectives to create new connections, leaving us fertile and open to new leaps of insight.

What are Plateaus, really?

Using our discussion of grokking in AI models as a weak analogy, a couple of things emerge that might explain why plateaus occur.

1. First, plateaus happen when your brain’s System 1 modeling of reality (the skill at hand) is stuck in a sub-par understanding and hasn’t yet grokked a better mental representation of the skill.

Often in machine learning, algorithms that descend a gradient to minimize the error in their modeling get stuck in what are called “local minima”, where they are somewhat good but not experts yet. When they settle into these little lazy sinecures they need to be prodded to escape the gravitational pull of their poor understandings/models to find better answers.

Like the AI that finally grokked, our System 1 brains may spend a long time in these sub-optimal states of understanding. Hence the plateaus. Generally speaking, our mental models of reality may just happen to be good enough to go through life awkwardly or blindly and we may lack the curiosity and intrinsic motivation to push to reach the next level of understanding, i.e., to seek the truth. This could be because it’s a tradeoff between usefulness and energy expenditure. We’ve evolved to conserve energy and our brains are energy hogs - rewiring the brain is super expensive. In fact, our brains use about 20% of our calories despite being only 2% of our body weight.

Despite this, we know that sometimes repetitive access to old and new information can suddenly show us new connections and shake us out of our complacent, wrong models to reach newer insights and better models of reality. We will later (in part 2) examine some tricks that may help create these new connections and force our mental models to upgrade themselves.

2. Second, our unconscious (system 1) understanding of something may be very different from the conscious (system 2) equivalent. For example, we may understand addition in a particular way when we are consciously doing the math or counting stuff out on our fingers, but once internalized, the unconscious brain may have its own alien model of addition that would be completely bizarre if we ever got access to our brain’s inner machinations. System 1 prefers a simple way to automatically do the right thing, and the specific method it uses doesn’t have to be explainable or match the ways that System 2 might process the same thing. Often we find expert performers who can do things that they simply cannot explain or teach others because at some level the System 1 model that they grokked became very different from their System 2 model. This is why even if you understand something at a conscious level, there may still be a long plateau waiting for you before you can internalize it into System 1.

Concluding Ideas for Part 1

To summarize and pull it all together, the basic idea we’ve been exploring is that System 1 cognition is instrumental in achieving the effortless grace found in Wu Wei mastery as described in Eastern philosophy. The more superior the model of understanding we’re able to incorporate into our System 1, the broader and deeper is your effortless mastery.

To create superior mental representations in System 1 requires deliberate practice (and not innate talent or rote practice). While sometimes we can skip System 2 and go straight to System 1 through rote practice, deliberate practice necessarily engages System 2 because the core of deliberate practice is all about analytical reflection from feedback. No one has named this phase transition from System 2 to System 1 yet, but this is essentially what results in our A-ha moments and mini-enlightenments that allow us to cross the plateaus. Also, our System 2 and System 1 understandings can be wildly different but similarly effective (in their own ways).

Finally, the place where most Journeymen give up on their path to Mastery is the long period of time where progress isn’t visible - i.e., the plateaus - where System 1 hasn’t yet undergone the phase transition to a superior mental model. This gives us some clues as to the kinds of tricks and systems we can use when sheer grit alone isn’t sufficient (or too painful) for us mere mortals to cross those darn plateaus.

Crossing The Dreaded Plateau and…

Unfortunately we’re already at 4000+ words or 20+ minutes of reading time. In the age of 10 second Tiktok attention spans, this is already way more than most people want to read in a sitting or two. My last essay was double this length and I have now learned to split things up. So, being mindful of your time, I will continue with the rest in part 2 of this essay: how to overcome plateaus.

Image credits: all the artists whose work is used by DALL-E to generate the images used here.

In fact, it turns out the vast majority of cognition happens in the mostly unconscious Cerebellum which was originally thought to be only concerned with lower-level things like sensorimotor control. But we now know that the Cerebellum has a much larger role to play in cognition. In fact, knowing that it has between 70-100 billion neurons compared to the much fewer 16-20 billion neurons in the Cortex should tell us something about the importance of its role in our brain.

While innate talent might give you a head start, it rarely is the reason why people attain mastery. Indeed, most world-class experts didn’t start out as prodigies and even those considered childhood prodigies, it turns out, had put in much more deliberate practice than the rest of us very early on in their childhood, before they were recognized as prodigies.

The term “grok” was originally coined by Sci-Fi writer Robert Heinlein in the 1960s to describe a kind of intuitive and empathetic understanding as possessed by some Martians in his novel “Stranger in a Strange Land”.

Great write-up and guide to learn and master new things -- applicable to the coming new year!

I read a couple books on these themes-- this is a good reminder to get back into it. I’m archiving this for when i have time to focus on it.